Interview with Shelly Sanders

- cplesley

- Jul 25, 2025

- 6 min read

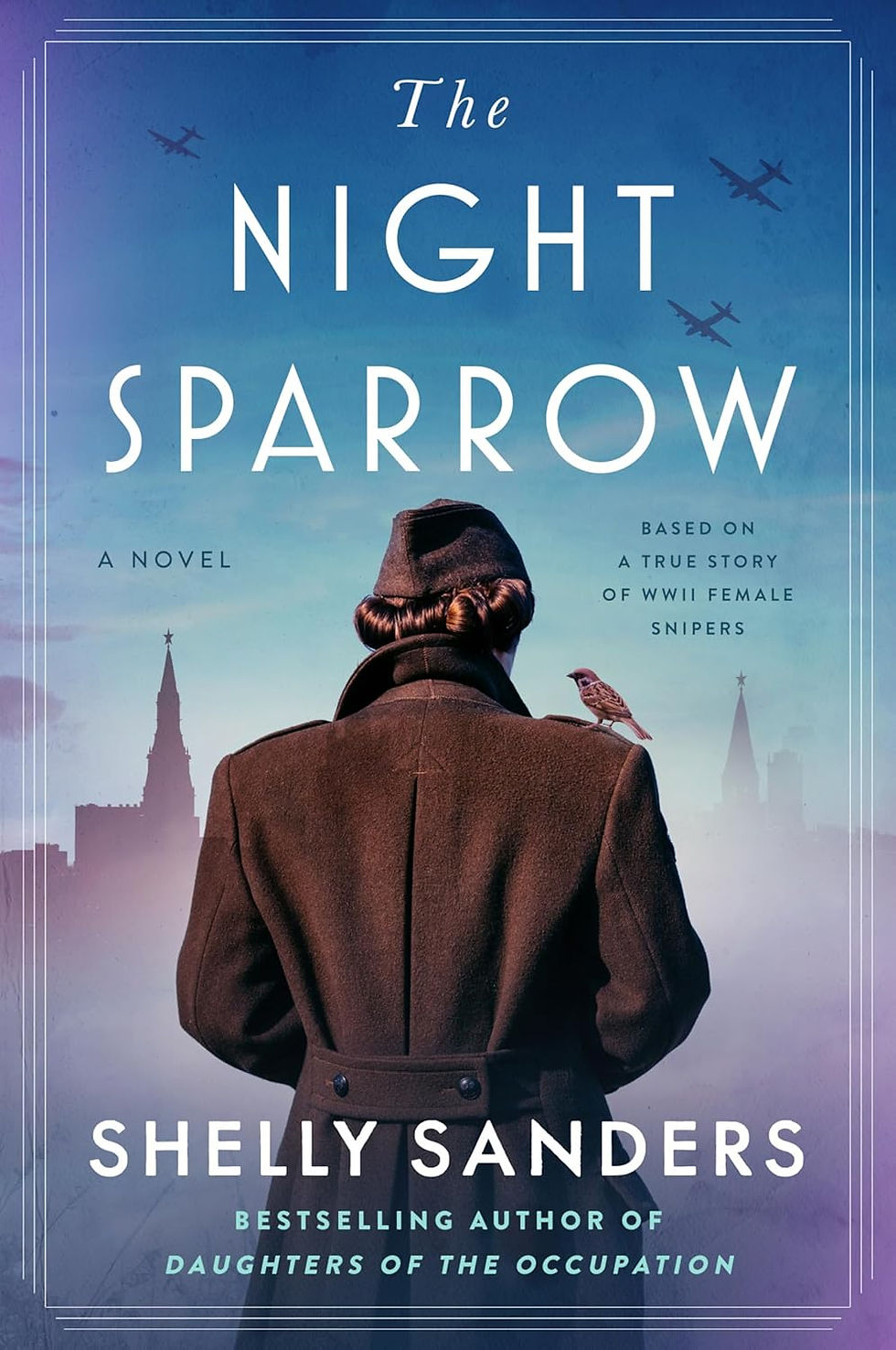

The juggernaut that is fiction set during World War II continues unabated. Several novels that have come my way have explored women’s participation in the Soviet armed forces, especially the all-female bomber pilots known as the “Night Witches.” In The Night Sparrow, Shelly Sanders takes a slightly different approach, examining elite female snipers in the Red Army and the many trials and tribulations they faced among troops who at times respected them but often abused them. The result is a fast-paced and engrossing tale. Read on to find out more from my interview with the author.

You have written four previous novels—three for young adults reimagining the life of your grandmother and another, Daughters of the Occupation, set in Latvia during World War II. What would you like readers to know about those earlier books?

When I learned that my grandmother’s family escaped a pogrom and fled to Shanghai, I had know more about living as a Jewish girl under the last tsar. My research led to The Rachel Trilogy (Rachel’s Secret, Rachel’s Promise, Rachel’s Hope) which parallels my grandmother’s journey. In researching these novels, I felt connected to my grandmother, who died when I was thirteen and more interested in boys than my heritage.

Daughters of the Occupation is a seminal book for me, as it is inspired by the transformative discoveries of my Jewish-Latvian roots, my great-grandparents’ exile to Siberia, my family’s Holocaust narrative, and the inter-generational trauma that has shaped my maternal line.

And what drew you to this story, also set in World War II but opening in Belarus?

During an online search for female heroes in WWII, I came upon Moscow’s Central Women’s Sniper Training School. As I began reading about these female snipers, I realized that everything I knew about war, I knew from a man’s point of view. I wanted to write a WWII novel that reflects a woman’s combat experiences.

My Jewish protagonist, Elena Bruskina, is driven by vengeance after losing her family and enduring the horrors of the Minsk ghetto. Soviet Jews also had to reconcile Stalin’s view that Soviet citizens were being targeted, even though ghettos and mass graves were filled solely with Jews.

When I discovered Masha Bruskina’s brutal hanging in Minsk, I had to include her story. Hence, the story begins in Minsk, Masha becomes Elena’s younger sister, and the ghetto and strong partisan movement drive the plot and Elena’s character arc.

Where is Elena Bruskina in her life when we meet her?

Before Germany invades the Soviet Union, Elena is studying German at university with plans to become a professor. Like all young people in the Soviet Union at the time, Elena is an experienced shooter from her time in the youth movement, the Komsomol. The Soviet Union dissolved gender barriers in the 1930s and encouraged young people to “know the rifle like they knew their ABC’s.” When Elena arrives at the sniper training school, she has lost her entire family, her home, and her identity. Elena craves vengeance but discovers that retribution takes many forms.

How does Elena’s experience in the Minsk ghetto shape her choices?

The Minsk Ghetto imprisoned 80,000 Jews in a small, fenced area with armed guards that were a looming threat. Elena witnesses Jews gassed in vans, hung in public, buried alive, and starved to death. Her burning need for revenge is ignited after witnessing her sister’s callous murder based on phony charges. Elena’s decision to escape the ghetto is kindled by the trauma she’s withstood.

She first joins the partisans. What is their role in the story?

Between 11,000 and 15,000 Jews escape the Minsk ghetto, and form the largest network of Jewish partisans in the Soviet Union. As a partisan, Elena takes part in anti-German resistance. This imbues her with the confidence to do more. But she needs a weapon to retaliate, and guns are hard to get, especially for woman. Upon hearing about the Women’s Sniper Training School, she feels ready to enroll because of her partisan experience.

From there, Elena transitions to the Red Army and a sniper unit. What is her training like?

The Central Women’s Sniper Training school is historically significant as the first of its kind anywhere, just as Soviet women are the very first female snipers in combat. Upon arrival, Elena’s hair is cut short and she’s given an oversized men’s uniform because women’s uniforms don’t exist. The bunks are rudimentary, with mattresses and pillows filled with straw, but she has clean sheets and towels. And the meals are plentiful, except they’re not given enough time to eat!

Every second day, Elena wakes at 4:30 am to march seven kilometers to the shooting range where the male commander, who calls them “useless girls,” teaches them how to dig different types of foxholes and trenches, to crawl on their bellies, to navigate terrain, to memorize landscape details, to set up firing positions, to camouflage themselves, and to shoot.

“We were shooting at targets which were full height, from the waist upwards, from the chest upwards, targets that were running and fixed, in full view and camouflages,” sniper Yulia Zhukova says in Avenging Angels: Soviet Women Snipers on the Eastern Front, by Lyuba Vinogradova.

On alternate days, Elena rises at 6 am for reveille, eats and returns to the barracks for ballistics theory, equipment training and military drills. Evenings are spent cleaning rifles and attending lectures.

Curiously, there is a great emphasis on singing while marching. One commander even orders them to crawl in the mud when they don’t sing on the way back from the shooting range. The female snipers continue this tradition of singing during marches on the front.

Women are accepted into the Red Army, but they aren’t always well treated. What can you tell us about the experiences of Elena and her comrades with misogyny and abuse?

The Komsomol youth group, which has long influenced women’s attitudes, implores them to remain “pure as virgins,” while Red Army commanders feel entitled to sexual relationships with their female subordinates.

These conflicting notions are underscored by men like Lieutenant Colonel Kolchak, who says, in 1943, “Young girls, twenty years old, what have they had a chance to see, the drills in our school? This is an unusual lifestyle for a girl. And such relations between the two sexes exist and you can’t do anything about them. We are all sinful people and I myself would be ready to serve during the day and carouse at night…”

Girls who report sexual assaults are either ignored or face worsening treatment from their abusers. A derogatory term, “Mobile Field Wife,” is introduced to draw attention to female soldiers having sex with married commanders, even if the women are forced into these “relationships.”

In her diary, Tatiana Atabek writes about being raped in the middle of the night: “I felt I had no strength to stop this person … and felt so insulted—I had never been so wronged in all my life—that I wept uncontrollably.”

The ultimate shame for women comes at the end of the war. While male soldiers are greeted triumphantly, the female snipers are called whores by wives awaiting their husbands’ return. Many of the surviving snipers are embarrassed to wear their medals and are, in fact, ordered to stay quiet about their achievements and return to their foremost duty, motherhood.

Elena’s ultimate mission in 1945, however, is quite different from what she’s trained for up to that point. What should readers know about that, and how does she qualify for this task?

I don’t want to give any spoilers, but I can say two things. First, when Elena is injured, she is re-deployed as an interpreter because of her fluency in German. There was a shortage of interpreters, and it was common practice to redeploy injured soldiers depending on their capabilities. Elena, an academic, is well suited for this role, which requires a quick mind and advanced language skills.

Second, Elena’s redeployment is inspired by a real-life Jewish interpreter, Yelena Rzhevskaya, who spent the entirety of her time in the Red Army as an interpreter.

What are you working on now?

HarperCollins has commissioned me to write a novel about an all-female aviation regiment in WWII. These aviatrixes are given the most antiquated aircraft—open-cockpit bi-planes made of canvas and wood—and they fly all night, without radios, harassing the Germans with bombs positioned under the bottom wings. It comes out in 2027!

Thank you for answering my questions!

Shelly Sanders is the Canadian bestselling author of The Night Sparrow and Daughters of the Occupation, and the award-winning young adult Rachel Trilogy. She enjoys writing about unsung women who changed history. Prior to writing historical fiction, Shelly was a journalist for many Canadian national publications. Find out more about Shelly and her books at https://shellysanders.com/.

Photograph of Shelly Sanders © Portraits by Mina. Reproduced with permission.

Comments