Connecting with My Characters

- cplesley

- Aug 11, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 5, 2024

Years ago, I wrote a post about plotters and pantsers, admitting that I was definitely in the latter category. For those unfamiliar with these terms, let me add a brief explanation: plotters figure out the main details of their stories—including the protagonists and what drives them—before they sit down to write; pantsers “fly by the seat of their pants,” diving in and allowing inspiration to take them where it will, trusting the characters to reach their destination in the end.

In real life, few people fall wholly into either type. I am still more a pantser than a plotter, not least because I’ve learned from experience that energy put into constructing a detailed plot is wasted where I’m concerned: five pages in, one character or another has thrown up a roadblock or wandered down a different and more interesting path. To paraphrase Lauren Willig, whose novels I love, the main value of an outline is that it gives me something to dismiss with a hollow laugh after realizing how little resemblance it bears to the published book.

Even so, in addition to researching background information, one step I always take before I settle before my keyboard is a search for my main character: who she is, what she wants, which obstacles will get in her way. (Not all my protagonists are female, but in my current series they are.)

I’m at that stage now. Anna’s story is far from completion, but close to a full rough draft. Moreover, over the course of several books, she has developed from a biddable little girl who appeared almost too good to be true into a shy but determined young woman, willing to fight for what she wants despite opposition from her family.

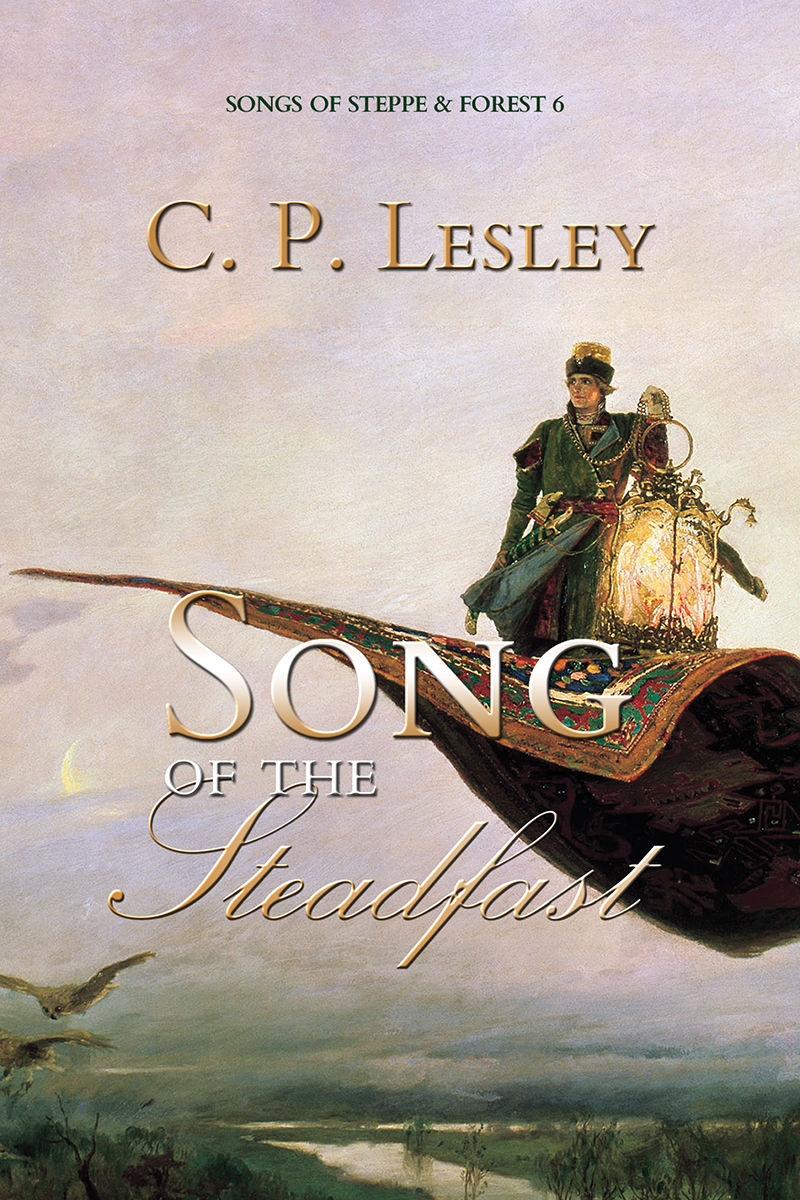

Song of the Steadfast concludes that particular plot thread. The characters will no doubt make cameo appearances in later books, but their days at center stage are drawing to a close, opening the fictional door for a new group of stars. And since the whole point of this series is to explore opportunities that existed for women beyond arranged marriages, I’m considering what as-yet-unexplored avenues to self-fulfillment might be available for this next book. So far, each of my heroines has found romantic love after doing the hard work of self-discovery, but I’m not sure that pattern will—or should—continue.

Whether the new heroine will agree remains to be seen. Grusha was supposed to choose her shamanic vocation over any personal tie except that of motherhood, but then Mansur showed up and the story veered off in another direction. Juliana, too, developed far warmer feelings for Felix than I’d imagined her capable of. These are examples of why I can’t call myself a plotter, but also of the delight in discovery that makes me enjoy writing fiction. After all, if I know exactly where a novel is going, what’s going to keep me interested for the year or more it takes to finish it?

So in the spirit of sharing, how do I approach an unformed story? This time around, I began with a rough and, as it turned out, inaccurate sense of place: years ago, I made the impulsive decision to set a story not in Kazan—which Ivan the Terrible conquered in 1552 using a combination of all-out war and twisted ideology bizarrely echoed in Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine—but in Astrakhan, a city on the northern shore of the Caspian Sea. Russia conquered Astrakhan, too, a few years after Kazan, and at the time I thought setting a novel there would be a way to address the destruction of the Tatar khanates in a setting virtually unknown to Western readers and mostly an afterthought even in Russian accounts.

With that goal in mind, because Astrakhan was also a stopping point along the northern Silk Road, I decided that my heroine would be a silk weaver. Another element of the Songs series is that not all the main characters are noble-born, so this choice allowed me to feature someone whom we would consider middle- or lower-class. I planted a seed by having Anfim, the hero of Song of the Sinner, talk about a young female captive he’d rescued on his journey down the Volga. The girl’s name was Kiraz, and she had appeared briefly in a previous novel as a timid child, but the only other thing I knew about her was that Anfim apprenticed her to a silk weaver in Astrakhan.

A couple of weeks ago, when I realized I had progressed far enough on Song of the Steadfast that I could start musing about the next story, I revisited the historical background and discovered that the “conquest” of Astrakhan was nothing like what happened to Kazan, never mind modern-day Ukraine. It was a spat between cousins that got out of control when first one, then the other, called on Ivan the Terrible for help. In response, Ivan sent an ambassador to accept the then-khan’s oath of loyalty. When the then-khan changed his mind, things went downhill, but every time things got nasty, the khan fled into the steppe. The residents of the city also ran away and hid until things stabilized. All of which was undoubtedly terrifying for them but rather a damp squib as a source of dramatic conflict.

I know that sounds callous, but I’m speaking here as a novelist, not my everyday self. Of course, in real life I want the best outcome, especially for the innocent, and the best outcome in a war is minimal casualties followed by a lasting peace. In fiction, though, if all the orcs do is show up at the castle gates and wave their flags before heading back to Mordor for dinner, readers tend to feel cheated. So it was back to the drawing board for me.

But while poking around looking for things I could use, I discovered that Khan no. 2, who replaced the guy who started the trouble but went on to cause just as much trouble of his own, ended the conflict by deciding it was time for him to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. (Like the rest of the Golden Horde, the population of Astrakhan was predominantly Muslim.) He left, the Russians moved in, and life for the locals more or less stabilized.

Now, I’ve been writing Muslim characters for fifteen years, and not one of them has made the hajj. I have always assumed that some of my characters did behind the scenes and others would in due course, but here was a chance to show someone who played a significant role in my heroine’s life making that choice in real time. Precisely because the trip was long and dangerous, a smart person would travel, if he had the chance, in the wake of the khan, protected by the royal guards.

At that point, I turned to one of my favorite novel-planning exercises, stolen from John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story: what if? The basic idea is to brain-storm a list of the most outrageous possibilities a character might encounter. Many won’t work, but a few will. And the exercise frees up the imagination, which itself exposes elements of the character that otherwise might remain hidden.

So I asked a series of questions. What if my heroine had married a silk merchant, who reached middle age and decided accompanying the khan was a chance to fulfill his spiritual obligations? What if this silk merchant had selected my heroine, who would be beneath him on the social ladder, not as his first wife but his second? What if he then brought in a third woman, fresh and new and chosen to keep him company on his journey? How would my heroine feel about being left behind?

Those questions led to new possibilities. Would the husband divorce her? Would she want him to divorce her? At twenty-six, she is young by modern terms but not by those of the sixteenth century. I’ve downplayed the issue of polygamy so far in my series; except for the leaders, nomadic Tatars were mostly monogamous because they lacked the resources to support multiple wives. But a wealthy silk merchant could afford to maintain more than one bride, and that would open up all kinds of dynamics among the women, especially if one produced sons and the others did not.

I’ve also started to look into silk weaving as practiced in Central Asia. To my surprise, it was conducted in family homes. Even the silkworms were raised in domestic settings, and many of the looms were small, portable things. Kiraz can, if she wants, pack up her dyed threads and her loom and seek out her family—perhaps in the company of a handsome (fickle?) Italian merchant on his way north. The glory days of Genoese and Venetian trade in the Black Sea were over by 1556, but merchants could still move around, as shown by the Englishman Anthony Jenkinson’s journey from London to Tehran and Bukhara and back in the late 1550s.

Kiraz will have to rely on purchased thread once she reaches her destination, because she won’t have space to transport thousands of silkworms, but she brings a useful skill with her, one capable of supporting her as she settles scores with her family. Her story then becomes one of reclaiming her heritage and establishing her own path, rather than simply accepting the hand life has dealt her.

These are rough ideas. I don’t know yet where Kiraz will go or how she will get there. But I know more than I did a month ago. Some of it may even make it into the final draft—always assuming Kiraz agrees to go along with the plan.

Images: Alexei Harlamoff, Girl in a Red Shawl (1880s) and Adam Olearius, Astrakhan in the 1630s, both public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Silk weavers at their looms from Pixabay, no attribution required.

Comments